Everything you need to know (and probably didn’t) about Ottawa’s mental health dept. becoming an authority

Although presented as a straightforward idea, the conversion to a CMH authority is more nuanced than it seems.

Story summary

- By the late ’90s, several counties moved to authority status to gain better control over their budgets and personnel. Ottawa County also considered converting then, and has revisited the discussion in the 30 years since.

- The county's administrators and attorney have indicated that the sudden urgency presented late last year was because of "time-sensitive" concerns about Medicaid deficits and increased costs — and who will cover the shortfall.

- There has been conflicting and confusing information since the issue was first presented in November, inspiring questions and concerns from the public.

OTTAWA COUNTY — Ottawa County is poised to convert its Community Mental Health department to a standalone authority, requiring only a majority vote on the county board of commissioners on Feb. 26 to make the decision official.

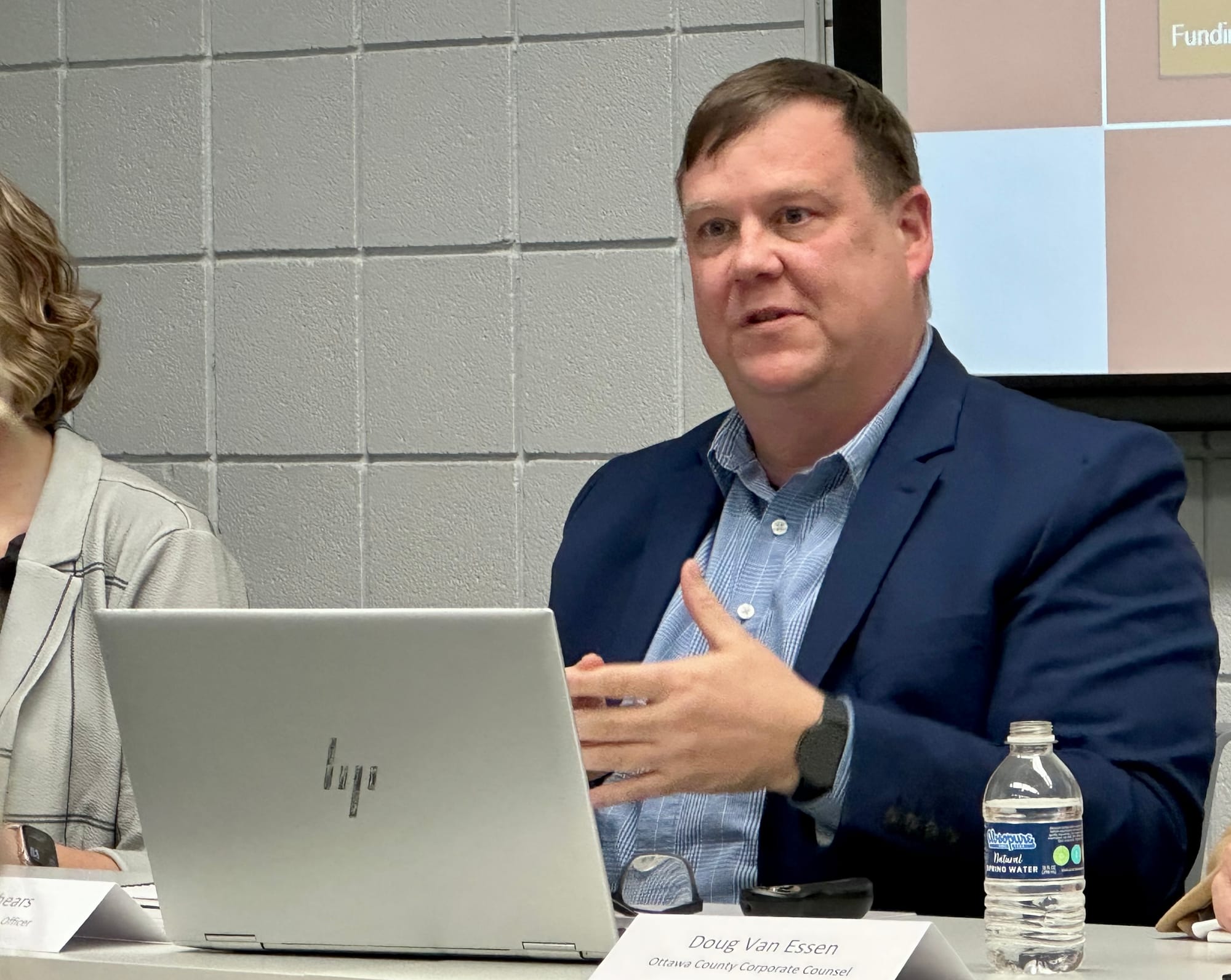

The topic was first officially brought forward in November, when CMH Director Michael Brashears and county corporation counsel Doug Van Essen told commissioners during a special meeting on Nov. 21.

However, the idea caught many off guard, as the officials were poised to vote to go into closed session — meaning the idea, the justifications and the process would have been kept from the public.

“I just want to indicate that trust is very important, and it's not been a strong suit in the last two or three years,” Park Township Melanie Scholten said at the special meeting. “So I'm hoping that you will take that to heart and try to gain some of that trust back for us. I'm also curious if there is an update on renewing the mental health millage that expires next year. We haven't heard any talks of if that's just going to expire, or if there's going to be any further talks of trying to renew that.”

Scholten’s confusion was reflected in several other comments at the meeting, noting that not all commissioners were even present, and that a regular board meeting had already been scheduled for the following week.

“I'm wondering why this meeting is happening at all when there is a board meeting scheduled two business days from now that's been on the books since January,” said Chantal Martineau, of Park Township.

“What is so urgent that you had to schedule a special meeting that apparently was given so little notice that two of your members couldn't make the meeting, and that the public was not able to hear about enough in advance to be able to show up,” she said.

Some commissioners — those in attendance — also seemed surprised, and insisted on keeping the discussion in open session.

“I think that there's reasons to decide for each of us to go into closed session, and there's reasons to entertain staying here,” said Commissioner Allison Miedema, a member of the far-right faction on board known as Ottawa Impact.

“Some of the things that I've thought about are protecting the public. I would say that the image factor is a big one for me,” she said. “Staff is observing us. It would be the public that we serve, its constituents that receive CMH services and weighing out if there's merit to going into a closed session first versus staying in the open. … I think that there's more merit in staying here in the open and letting just everyone hear the discussion that takes place.”

That led to a failed vote to go into closed session and a presentation on what it would look like to convert to a CMH authority and some of the justifications as to why.

In the months since, the board voted — a split decision — to host three public hearings on the issue in January and February, with mixed feedback from the public, with many noting a lack of justification that matches the sense of urgency that was presented in November.

“My big concern is the reasons given for the conversion and the lack of evidence to support that reasoning. Along with that, I’m not seeing any county commissioners or the CMH board question that lack of evidence,” Sheila Detloff, of Holland Township, said at the Feb. 5 public hearing.

“Everyone seems to just be taking the claims of Mr. Van Essen and Dr. Brashears at face value. And while certainly they both have expertise, they also appear to me to be heavily biased in favor of converting to an authority. As some of you know, my motto for this year is trust but verify. And so I’m here tonight to ask the county commissioners to trust but verify before you approve this conversion.”

Although presented as a straightforward idea, the conversion to a CMH authority is more nuanced than it seems.

Here’s what to know:

The idea for authorities divided officials, residents

The conversion of CMH departments into independent authorities was made possible by Public Act 290 of 1995, which went into effect on March 28, 1996.

The legislation was a major rewrite of the Michigan Mental Health Code; it decentralized the system by allowing CMH programs to choose one of three structures: a county agency, a multi-county organization or an independent authority.

Then-Gov. John Engler supported the legislation, saying it would modernize Michigan's mental health system by shifting power from the state to the local level, requiring mental health boards to have at least four of 12 members who are family members or actual consumers of mental health services.

Engler championed the requirement that service providers use "person-centered planning," which he argued gave individuals "choice and direction" over their own care rather than having a plan dictated to them by the state.

He also emphasized logistical and financial advantages, as authorities could bypass the county administrative processes and respond more quickly to local needs. The law also allowed CMH boards to carry forward up to 5% of their state funding into the next year, a provision Engler supported to encourage fiscal responsibility and long-term planning.

Not everyone was supportive of the legislation, however, with critics arguing that while the law provided the structure for community care, it was simultaneously used to justify the rapid closure of state facilities without providing the necessary long-term funding to support the "authorities" in their new roles.

In 1991, The Ann Arbor News noted that, as of 1965, there were 17,000 people in state-operated psychiatric facilities and another 12,000 with developmental disabilities were under institutional care.

As of 1991, however, 67,000 people were waiting for mental health services, with the state set to shutter state-run facilities in Newberry, Coldwater and Muskegon by the next year.

“Michigan can scarcely afford to lose the state hospital beds at Northville,” Kathleen Gross, executive director of MPS, told Psychiatric News in 2003. “The outgoing administration has always pointed to unfilled private psychiatric hospital beds to justify the closing of state hospitals. But many private beds licensed by the state are affected by managed care and the cash-strapped community mental health system.”

While the public-facing argument for Public Act 290 was "consumer empowerment," the behind-the-scenes struggle between state lawmakers and local officials.

Before PA 290, CMH directors were often appointed directly by the county commission, effectively making them county department heads. Lawmakers and advocates argued that directors were sometimes pressured to make clinical decisions based on county political priorities or budget shortfalls.

By converting to authorities, the CMH board (not the commissioners) gained the power to hire and fire the director. Although commissioners still appoint the board members to the CMH board of directors, they lost the "direct line" of control over day-to-day operations.

The legislation also was highly criticized by organized labor.

The American Federation of State and Municipal Employees, which in 1995 had been “battling the Department of Mental Health for nine years to force collective bargaining with group home workers around the state,” said the state was rewriting the mental health code to avoid collective bargaining with unions, The News reported in August 1995.

A major point of debate was creating an "arms-length" distance between the county's general fund and the CMH budget.

County commissioners were often wary of the massive financial risks associated with mental health, with often-unpredictable Medicaid costs year to year. The new law allowed them to "spin off" the CMH into a separate legal entity that shielded counties from the CMH’s debts or lawsuits.

A funding model under constant evolution

In 1963, Michigan enacted Public Act 54, its first Community Mental Health Act, which allowed counties to form local boards. Funding at that time was split 60-40 between the state and county departments.

In 1965, the federal Medicaid program was established, which eventually became the dominant funding source for the system.

In 1974, Michigan enacted its Mental Health Code (Public Act 258). It remains the foundation of the current system and shifted the funding match to 90% state and 10% local, making it easier for counties to expand services.

Read More: A Little History Worth Knowing Community Mental Health Services Providers in Michigan

In 1998, Michigan received federal waivers to move to a managed care model, where funding shifted from "fee-for-service" to capitation, a fixed monthly fee per Medicaid enrollee.

Initially, almost every individual Community Mental Health Services Program (CMHSP) acted as its own PIHP. The state stopped paying for every single doctor's visit (fee-for-service) and instead gave these PIHPs a fixed monthly "per-capita" budget to manage all Medicaid behavioral health needs in their area.

Since 2014, the state has had 10 PIHPs, regional entities that manage mental health, substance abuse and disability care that are divided up by regions of the state to distribute millions of dollars in Medicaid funds. They offer a range of services for everything from those battling substance abuse disorders to those with developmental disabilities.

In 2024, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services tried to enact a plan to consolidate the existing 10 PIHPs in the state down to three and open the system up to private bidders.

The consolidation move was made after five PIHPs did not sign a new contract after the state added several unnegotiated amendments with which they don't agree, which included uneven pay raises for care workers and no guarantee the state would pay the rate difference, along with reducing the risk reserve below what actuaries determined was needed.

Please consider becoming a monthly donor!

The PIHPs that declined to sign contracts with the state starting in fiscal year 2025 — from Oct. 1, 2024, to Sept. 30, 2025 — account for half the PIHPs in the state and include Ottawa County’s PIHP, known as the Lakeshore Regional Entity.

The transition clause of the latest contract they signed runs through September 2026, so the state determined changes were necessary to ensure beneficiaries are covered under an active contract, said Kristen Morningstar, the state bureau administrator of the department's Bureau of Specialty Behavioral Health Services.

The administrator also said separating the PIHPs and CMH would eliminate any conflicts of interest, because PIHPs are not effectively overseeing whether CMH is providing medically necessary services, The Detroit News reported in September.

The federal government will not approve Michigan's behavioral health Medicaid waiver until Michigan takes drastic steps to fix the conflict of interest problems, Morningstar said, which puts the state at risk of losing federal Medicaid funding.

After the five PIHPs didn’t sign the state’s contract, the state responded by issuing a request for proposal, or RFP, in August 2025 that allowed for both private and public entities to apply to take over handling of the state's PIHPs and mental health services.

Four of the five non-signatory PIHPs sued the state over the RFP — West Michigan’s LRE PHP was the one region that didn’t sign on to the litigation, claiming the language of the request made it impossible for them to apply.

Bidders could only bid if they provided services throughout the entire region, and they argued that the way it was structured made it impossible for them to apply. They also say the proposal will create a more bureaucratic and costly framework of services, making Community Mental Health agencies across the state unable to continue providing services in the way they have in the past.

In January, a judge ruled that although the state had the right to consolidate the number of PIHPs, the RFP language that was issued in August violated Michigan's mental health code because it prevented CMH agencies from fulfilling their statutory requirements to use Medicaid funds to provide services to people who could not otherwise pay for them by having financial contracts with providers.

By the end of January, MDHHS rescinded the RFP “to evaluate next steps and available options in alignment with our commitment to ensuring Michigan’s behavioral health system is structured in a way that best serves beneficiaries” while aligning with federal and state requirements, Bridge Michigan reported, leaving the 10-region public PIHP structure in place for the foreseeable future.

Earlier this month, the Trump administration issued — and then reversed — a sweeping decision to cut $2 billion in mental health and addiction programs.

The move put Ottawa County’s Recovery Court in immediate jeopardy, threatening programming that accepts defendants convicted of non-violent drug- or alcohol-related felonies in Ottawa County’s 20th Circuit Court.

Read More: Ottawa Recovery Court leaders: Abrupt revocation, restoration of grants prompts concerns

Nationally, cuts to Medicaid outlined by the “One Big, Beautiful Bill” passed last year are expected to cost about $900 billion over the next decade. The cuts were part of major reductions in federal health care spending to offset part of the costs of extending expiring tax cuts.

Timeline of mental health funding in Michigan

- 1963 (Public Act 54): Michigan passes its first Community Mental Health Act (six months before the federal version). It allows counties to form local boards. Funding is split: 60% state and 40% local.

- 1965: Medicaid is established federally, which will eventually become the dominant funding source for the system.

- 1974 (Public Act 258): The Michigan Mental Health Code is enacted. It remains the foundation of the current system. It shifts the funding match to 90% state and 10% local, making it easier for counties to expand services.

- 1981: The state begins "full management" contracts. Instead of the state managing the budget for patients in hospitals, counties are given the money to manage it themselves. If they can treat someone in the community for less, they keep the savings to expand local services.

- 1980s-90s: Massive closures of state psychiatric hospitals occur as Medicaid funding for community-based "rehabilitation" and "habilitation" services grows.

- 1995 (Public Act 290): The Mental Health Code is updated to allow CMHs to become "authorities." This gives them more financial independence from the county general fund.

- 1998: Michigan receives federal waivers (1915b/c) to move to a managed care model. CMHs become Prepaid Inpatient Health Plans (PIHPs). Funding shifts from "fee-for-service" to capitation (a fixed monthly fee per Medicaid enrollee).

- 2002: The state consolidates the system into 18 PIHP regions to manage financial risk.

- 2012: Public Acts 500 & 501 require Substance Use Disorder (SUD) funding to be merged into the PIHP system.

- 2014: The state further consolidates into the current 10 regional PIHPs.

- 2016 (Section 298): A controversial legislative proposal attempts to hand the entire mental health budget over to private Medicaid Health Plans (HMOs). It was eventually defeated after massive advocacy from the CMH system.

- 2024-26: The "SIP" (Specialty Integration Plan) attempt. MDHHS tries to consolidate the 10 PIHPs into three and open the system to private bidders.

- January 2026: A court ruling halts the state's plan to privatize the system, maintaining the public, 10-region PIHP structure for the foreseeable future.

Why did they convert?

By the late ’90s, several counties moved to authority status to gain better control over their budgets and personnel. Oakland County CMH and Van Buren County, for example, both converted in 1999.

As of June 1997, more than half of the county departments in the state had converted. Today, only five of Michigan's 46 Community Mental Health Service Programs operate as departments.

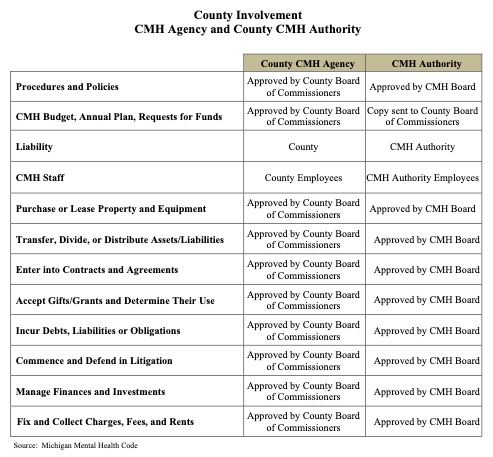

The shift from a department to an authority changed the legal status of these organizations. As authorities, they:

- Become separate legal entities from the county government.

- Can employ their own staff (who are no longer county employees).

- Can own property, enter into contracts and accumulate assets independently.

- Gain the ability to manage their own liability and insurance separate from the county's general fund.

Conversely, some county commissions resisted the change because they didn't want to lose control over a large portion of their workforce. Transitioning to an authority meant CMH staff were no longer county employees, removing them from county-wide union contracts and personnel policies.

Kent County’s CMH system, for example, adopted the name "Network180" in the early 2000s as part of a rebranding effort to signal a shift toward a "network" of private providers rather than a single government clinic. It waited, however, to officially transition to an authority until 2014.

The Detroit-Wayne County Community Mental Health Agency in Wayne County actively fought conversion until 2013, and it took the legislature passing additional bills (Senate Bills 1195 and 1196) specifically designed to force the conversion if the county didn't do so voluntarily.

Counties also have the option to convert back to a CMH department if they so choose.

That happened in Washtenaw County, which originally transitioned to an authority in 2000, but the county commission voted to bring it back in-house in 2015, citing financial inefficiencies during a period of state-level funding volatility after then-Gov. Rick Snyder created a new way for how funds flowed into counties.

Ottawa has considered this before

Ottawa County contemplated converting from a department to an authority once PA 290 went into effect in 1996.

Al Vanderberg, who was Ottawa County’s administrator from 2003 to 2021, said the county has considered the question of conversion periodically since the legislation went into effect in March 1996.

“We looked at this issue several times over the years,” Vanderberg said. “I recall discussions around 2007, and of course, the study that was published in 2016.”

Vanderberg said the circumstances over the years weren’t right to justify a conversion, but the funding model from the state has changed since the 2016 study concluded a conversion wasn’t financially justifiable.

“A lot has changed since 2007,” Vanderberg said.

The 2016 study was conducted by the office of Planning and Performance Improvement, now known as the Department of Strategic Impact.

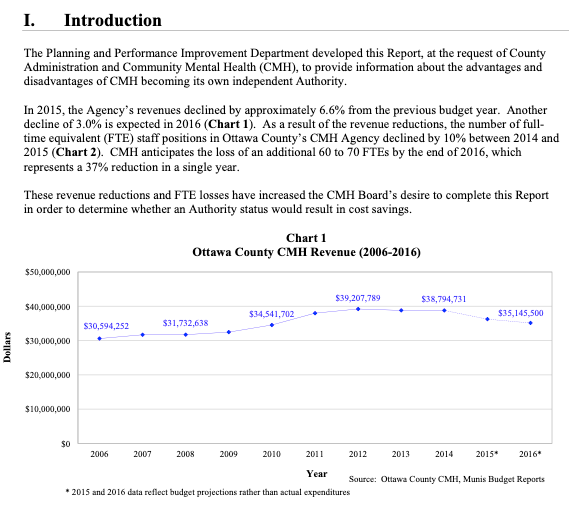

In 2015, the county’s CMH revenues declined by approximately 6.6% from the previous budget year and another decline of 3.0% was expected in 2016. This led to a 10% reduction in the department’s full-time employees between 2014 and 2015; at the time, it was anticipated that CMH would lose another 60-70 full-time employees by the end of 2016 — which would have resulted in a 37% reduction in the department’s workforce in a single year.

The 2016 study noted more disadvantages than advantages, noting diminished levels of administrative services, legislative advocacy and training opportunities, along with increased exposure to liability “for financial matters and negligence.”

Ultimately, though, it was the cost that led the county to decide not to convert.

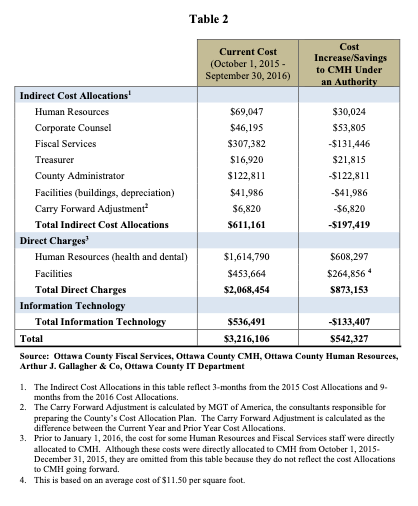

In government contracting, direct costs are expenses explicitly traceable to a specific contract (e.g., direct labor, materials, travel), while indirect costs are shared overhead expenses (e.g., rent, utilities, general admin) that support multiple projects.

While the county said there would be nearly $200,000 in savings on indirect costs, direct costs could exceed $870,000 per year.

With some savings projected in technology services, the county ultimately estimated that converting would cost the county more than half a million dollars per year.

“The benefits of CMH becoming an authority include greater autonomy in administrative and financial decisions. These include entering into contracts, accepting grants, making procurement decisions, and other financial and administrative aspects that could allow CMH to become somewhat more streamlined,” the 2016 study noted.

“However, included with that increased autonomy are a number of potential disadvantages to consider. As an authority, CMH would experience a diminished level of administrative services (e.g. human resources, fiscal services, etc.) compared to the services they currently receive with the county in a number of areas. There would also be a potential perceived loss of accountability by consumers. Additionally, CMH would become the liable party for financial matters and negligence,” the study said.

“There are several potential benefits of CMH becoming an authority; however, the potential disadvantages largely outnumber the benefits,” the 2016 study concluded. “With the potential increase in cost, significant increase in liability, and the potential decrease in service levels from human resources, fiscal services, and other administrative departments, the decision will be one that has important implications for CMH in the future.”

Ultimately, the county board of commissioners decided there weren’t enough net benefits to convert.

So, why now?

At the Ottawa County special meeting on Nov. 21, new Administrator Patrick Waterman said he was told that the conversion to a CMH authority was in process shortly after his hiring was announced on Sept. 12.

“After I was hired, kind of officially, I was coming in to meet with staff and department heads to kind of see what are the big issues, the challenges facing the county,” Waterman told commissioners. “One of the issues that was brought to my attention right away was this concern about funding risk related to Medicaid as it relates to CMH services.

“And this is a long-standing issue, that is my understanding, that the county has talked about for a long time. We've looked at the opportunities of transitioning to an authority. As you'll see, we're one of very few counties that still run CMH as a department, and so the overwhelming message was to me, coming in, we should be looking at this. It's a big priority. The landscape is changing. It's changing very quickly, and it puts the county at risk for a number of reasons, and that's what we're going to talk about today,” he said.

When asked why the matter was so urgent to address, and why it couldn’t wait until the board’s next regular meeting, Waterman indicated that behind-the-scenes discussions were taking place.

“We believe this is a time-sensitive conversation, and that's all I'll say,” he said. “It is a pertinent conversation to have sooner than later, and even though it's a couple days, we thought this is a pertinent conversation to have as soon as possible.”

Van Essen, the county’s longtime lawyer, said the purpose of the closed session was merely to feel out commissioners’ appetite for converting, meaning a conversation would come later.

“I just want to assure the public that the issue today is not to debate a department versus an authority model,” he said at the Nov. 21 meeting. “The only reason we were going to go into closed session is to have perhaps more candid discussion about whether or not the board is even interested in starting the debate.”

Van Essen highlighted the fact that, as of November 2025, Ottawa County was facing a $5.5 million deficit as well as noting the funding instability at the state and federal levels.

In fact, Brashears, the Ottawa CMH director, told his board just before the special meeting with the commissioners that a region-level revenue update had reduced Ottawa CMH's expected Medicaid revenue by about $2.8 million, which expanded the agency's projected deficit.

“Anyone watching the news will realize that both the Republicans and now even the Democrat administration of our state are realizing that we can't continue to go on with Medicaid and Medicare as presently constructed,” Van Essen said. “So the likelihood that if we're having a problem now, we may have even bigger problems in the future is imminent.”

The biggest drivers of the shortfall:

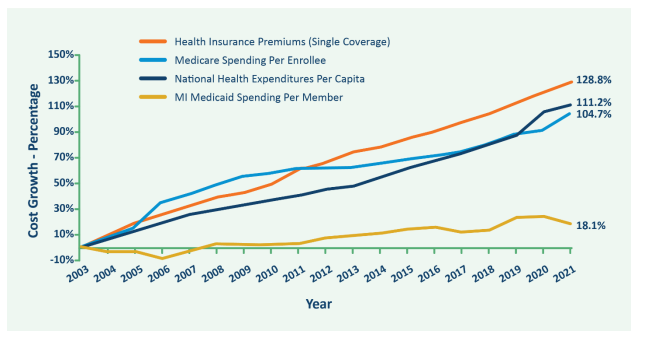

- State funding decisions: MDHHS has utilized actuarial data that is often two years old. Local officials argue this fails to account for current inflation and the actual cost of care today.

- Increased demands: There has been a sharp rise in the need for high-cost services, particularly in residential care, autism services and crisis intervention.

- Medicaid "redeterminations": Following the end of pandemic-era federal protections, many residents lost Medicaid coverage during the re-enrollment process, reducing the total revenue flowing into the local system even as the demand for services remained high.

Van Essen explained that when Medicaid started moving to a managed care model in Michigan — where the state pays private insurance companies a set monthly fee instead of paying doctors directly for every visit — things started to get a bit complicated.

“If you have 300,000 people, you're going to get funding for each person. Now, the model is we get a certain amount of funding for everyone on Medicaid. Within that funding, you have to provide certain entitlement services. The obligation is on you to make that work. And if you can make it work and have a little bit of extra, you get to keep it. But if you don't make it work, you have to absorb the deficit,” he said.

He explained that prior to the PIHP system being put into place, counties could carry forward profits to place in an internal service fund, or ISF, in order to have a sort of rainy day fund during lean federal funding years.

“So we would take our profits from one year, and if we had a deficit the next year, we could cover it,” he said.

There still is an ISF, Van Essen said, however, it’s now managed by the Lakeshore Regional Entity, one of the 10 state PIHPs of which Ottawa is a member; six other counties are in the LRE, including Allegan, Kent, Lake, Mason, Muskegon and Oceana.

“There is some reserve from the profits of the seven counties into that, so if one county has a deficit, you have that bank,” he said. “So that's the concept of managed care, and if we have a $5.5 million or more deficit, we're going to ask the LRE to use its internal service fund to cover that. The concern is, do they have it? I'm not sure they do. Then what happens?”

“The issue is multifaceted, and part of it is framed by budget shortfalls, where the local CMH agency has, over the last couple of years, spent more money than the region has allocated to us,” said Tom Bird, CMH board chair. “The demand is here. The people we serve, many of them have high needs that are expensive to deliver, regardless of whether it's a county department or an authority.”

Bird said a big concern is that the reserve fund in the LRE is getting smaller and smaller.

“The pooled ISF fund for the region is diminishing every year, and we're thinking within two years that fund will be depleted. What happens then? Well, nobody knows,” he said. “Is there a pool between LREs, where, if this LRE uses all of its reserves, Kalamazoo contributes some of their reserves to make us whole? Nobody knows the answer to that. And then the question is, let's suppose all those funds across the state are depleted. Does the state then have to come in and make up the difference, or is the county liable for that?”

The future of CCBHCs

Another factor is the state’s Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics, or CCBHCs, a federal grant‑driven model layered on top of existing CMH/Medicaid systems that is designed to support a more comprehensive outpatient behavioral health “clinic” model.

Michigan, which has more CCBHCs than any other state, Bob Sheehan, CEO of Michigan’s Community Mental Health Association, told ONN in late January.

“It's a great model. It ensures access to all: Medicaid, non-Medicaid, commercial, uninsured, to get care. However, it requires enough workforce. And, in some parts of the state, there's a workforce shortage — behavior, health everywhere. In some parts of the state, especially rural, it's really thin, and so those folks have said, ‘I don't have the staff to do this,’” Sheehan said.

Sheehan said another drawback to the CCBHC program is that it covers nine essential services, “but they're all outpatient, so it doesn't include residential care,” something that is in short supply statewide. “It doesn't include anything for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD). IDD is half the mental health budget in Michigan, so it doesn't include half the budget, nor does it include inpatient and residential for the folks on the mental health side.

Sheehan said managed care isn’t perfect, but it’s better than the old system.

“So it's not a perfect solution, but it's really good … but it has to be married to the risk bearing,” he said. “And I say risk-bearing because what you don't want is to go back to the old fee-for-service system, where I'm only paid as a clinician when I see you, whereas I can keep you stable if I talk to your landlord or your mother or your doctor.

“But if I'm only paid when I see you, then I won't do those things. And that's why commercial insurance doesn't tend to cover chronic mental health conditions — because they're used to office-based package business for psychotherapy. So we have to keep that system in place,” he said.

Van Essen told commissioners in November that the CCBHC grant program has no reserve.

“You're given a certain amount of money, you have to provide a certain amount of services, and hopefully you'll be able to make it work,” he said. “But, as an entitlement program, if you take that money, you have to provide the service. If you can't find people to do the service at a certain rate that you're expecting, you can have a deficit, and there's no LRE ISF or county ISF for the CCBHC program — high risk.”

Brashears, the Ottawa CMH director, said the state has to renew the CCBHC demonstration project in 2027 with the federal government, which is an unknown outcome.

“Indications are we don't see any threats to it yet, but you never know,” he said.

He explained that the county receives 12 equal payments from the LRE to provide the entire Medicaid services array, from those with significant disabilities, mental illness, those who are intellectually and developmentally disabled, as well as those with significant mental health issues.

“Regardless of the number of people we serve, the revenue never changes,” he said. “You have to meet all of their medically necessary needs with the same dollar amount. So it assumes that you're funded adequately in the revenue side to meet the benefit that you're managing. Unlike private sector managed care companies, we cannot deny care. I must provide the service for any Medicaid recipient in that program that meet medical necessity, regardless of revenue, as long as they live in Ottawa County.”

Pleading with the state

Brashears, who testified before the Michigan House’s Appropriations Subcommittee on Medicaid and Behavioral Health last year on the shortcomings of the current state funding model, said the difference between staying on budget or blowing it could boil down to a handful of recipients who need expensive services.

“We have some clients where their benefit for one individual could be a million dollars a year based on the type of services they need … not a lot, but all you need is three of those and your budget's gone,” he said.

Van Essen said he has tried to get the state to confirm that it will cover a deficit if the county were to remain a department; he received no answer, which prompted worry.

“I sent two letters to the state of Michigan, and the first I said, ‘We're happy to do your managed care for you. We just want you to clarify that, should there be a deficit in that program, our county taxpayers are not obligated to pick up your Medicaid responsibilities to the federal government. Crickets,” he told commissioners.

He said he then “upped the ante” and said the county was actively considering converting, “and we need to know whether, if we continue in these programs, you're going to be the underwriter. And if you're not going to be the underwriter, we don't want our citizens to suffer. Crickets.”

He said he finally received correspondence from the Attorney General's office saying it was “looking at the legality” that he presented in his letter because, “I offered a legal opinion that the general fund of Ottawa County … there's no authority for us to be the underwriter of an entitlement program. That's not what our taxpayers have signed up for.”

Despite having held the longtime legal position that the county’s general fund cannot be used to cover Medicaid shortfalls, Van Essen said he still had cause for concern — even though there is no tangible threat from the state or litigation against the county.

“We are still vulnerable if we continue to go forward, and even though I believe that legal opinion is correct, there are no guarantees when you get into the court system and you're dealing with highly politicized judges at the upper levels that the right decision’s actually going to be made,” said. “And so you have to understand the risks that we have going forward and the statutory opportunity that we have to protect our taxpayers.”

Pros, cons and what would change

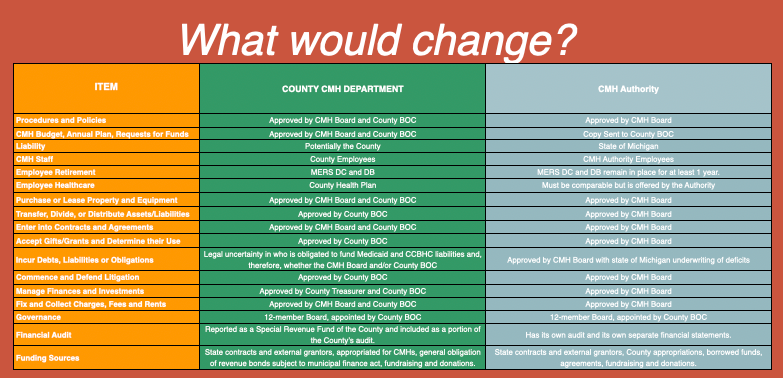

A key reason for counties to convert is that authorities have greater autonomy, which allows them to make swift decisions without waiting for a county board of commissioners' approval for every contract or hire.

“Authorities are kind of a quasi-arm’s-length relationship from the county. I say ‘quasi’ because the county commissioners still appoint the board for the CMH, and that board hires the CEO, so they kind of still have control, and they also have the obligation to finance the 10% match required in state law,” Sheehan said.

They can also seek specialized expertise for their organization.

“There is a specialty hiring advantage, because the CMH is a specialty business,” Sheehan said. “It's a large clinical operation … and they can actually hire and recruit into positions, sometimes with pay at different levels that you wouldn't expect in a county.

Authorities also have the power to engage in short-term borrowing to manage cash flow — a critical tool when dealing with delayed state or federal reimbursements.

“One of the advantages for the authority is that it can actually take on debt; currently, departments themselves can't take on debt,” Sheehan said. “The county can, but sometimes that's not in the interest of the full county to take on debt.”

Authorities also have the option to leverage the county’s bond rating to take on debt, which could be used for things such as capital purchases, building repairs, buildings themselves and equipment, Sheehan said.

The primary driver, however, for most counties to convert is the reduction of financial liability. Deficits in Medicaid entitlements for an authority are generally covered under the state’s multi-billion dollar budget rather than the county’s smaller local budget — however, this has proven to be a gray area, both Van Essen and Sheehan said.

“It does shield the counties somewhat; this is where it's not so clear from a litigation risk,” Sheehan. So if a client sues the CMH, and the CMH is part of the county government, they're just suing the county. So the county has liability for clinical practices, where in an authority, that line is clear.”

What's not clear, or less clear, is the financial risk, Sheehan said.

“So if a CMH has financial problems, and they're an authority, in most cases, the counties have said to the authority, ‘Best of luck. I hope that goes well,’ and they haven't jumped in. But it's the county departments … they have to jump in. The county somehow subsidizes them, so let’s keep them running.”

One uncertainty, however, for CMH becoming an authority is the other side of the coin, he said.

“So, if CMH needs money under an authority, they have to make proposals to the county, as opposed to the county department, which the dialogue is much more internal.”

Drawbacks to converting are that, while the initial transition process takes 9-12 months, according to Van Essen’s timeline estimation, the full switch often involves a multi-year process as the authority negotiates the transfer of buildings, software licenses and equipment from the county.

Another disadvantage is the loss of shared inter-departmental services, such as HR, accounting and legal services across multiple agencies. An independent authority likely would need to hire its own specialized staff or pay the county for these services via contract, which can sometimes increase overhead costs in the short-term — a finding that was identified in the county’s 2016 conversion study.

How would employees be affected?

The biggest question, however, is how the change would affect CMH employees.

While state law protects employee wages and benefits for at least one year after a conversion to an authority, there is no guarantee of wages and benefits — something that was a significant priority for CMH employees when they unionized in 2024 during the tumultuous tenure of far-right group Ottawa Impact, the controlling majority on the board of commissioners.

The union

Most recently, the board of commissioners voted to extend the contract with the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, or AFSCME, which represents the county’s CMH employees.

Another unknown is the fate of the CMH union contract. Although a new authority would be required to honor any existing contract the employees have with the county, new contract negotiations likely would begin as soon as the change took place.

The motion is to extend the contract with AFSME and CMH of Ottawa County, according to the terms of the collective-bargaining agreement and extend it.

— Sarah Leach ☮️ (@ONNLeach) January 28, 2026

Approved unanimously.

Clark Cunningham-White, a social worker at Ottawa County CMH and the local union representative for CMH employees, said he and fellow employees had “mixed emotions” about transitioning to an authority.

He said he had “high regard” for the county’s fiscal and purchasing teams, but that he found the contract processes to be “inertial.”

He also said he wasn’t going to defend the status quo as perfect.

“My experience last year of moving to a newly rented office, with month after month of delays, showed current choke points in how the county engages with other local government agencies and private businesses,” Cunningham-White said.

Key questions that have arisen in public hearings the county hosted in January and February revolved around wages, the union contract and the CMH pension fund.

“For our employees, the statute offers protections,” Van Essen said Nov. 21. “We cannot diminish their wages for at least a year.”

“Protection for employees, employees who are now county employees, would transition to the authority with the same benefits, the same medical health plan under MERS. So there'd be continuity of staff,” said CMH Board Chair Tom Bird. “You don't want to wind up losing your staff if you have a transition, the heartbeat of the organization.”

Van Essen said CMH employees likely would benefit from competitive wage comparables with the private health sector and no longer having to adhere to the county wage structure — eventually.

Ottawa County’s CMH follows a wage structure established by the county’s Universal Wage Scale, which categorizes positions into specific pay grades. The county is currently in the final stages of a comprehensive wage study, with preliminary results published earlier this month.

“We've done a wage study, where they're getting compared to non-medical providers that work in the county long-term,” Van Essen said. “Their comparables are other medical care providers in the community, mental health, business. So long-term, it's more of a view that these are medical care providers, not Ottawa County governmental employees. I think as time would go on, they would be paid like medical care providers. You have a squaring of the market and CMH, which probably will benefit our health care providers in mental health.”

Pensions

In addition to the wage scale, employees also had questions about their pension plans.

The 2026 conversion study noted that Ottawa CMH currently contributes approximately $1.6 million per year to the debt service on an outstanding pension bond through a payroll allocation.

That annual contribution exists because of a financial strategy the county implemented in 2014 to address its unfunded pension liabilities.

In late 2014, the county issued approximately $29.3 million in general obligation pension bonds, using the bond proceeds to pay down a large "unfunded liability" managed by the Michigan Employee Retirement System defined benefit plan, or MERS.

MERS is an independent, professional nonprofit organization that provides, administers and manages retirement plans and related services for over 1,000 Michigan local units of government.

Although the bond was issued by the county as a whole, the debt repayment is distributed across the departments whose employees participate in the pension plan, with $1.6 million being the remaining portion of CMH’s "fair share" of that. It is calculated as a payroll allocation, meaning a percentage is taken out of the CMH budget based on total staffing and historical pension liabilities.

Because CMH is a county department, it can use Medicaid and state grant funds to pay this allocation, which effectively allows the county to use state and federal mental health dollars to help pay off the 2014 pension debt.

If CMH were to become an authority, the change would free up that money, however, the county would now have to find that money from another source to cover the debt.

“Immediately, when CMHOC becomes an authority, they will no longer contribute Medicaid and grant funds to the remaining three years of outstanding pension bond payments which will free up a significant amount of operational capital,” the 2026 study said. “Conversely, the county will need to fund this contribution from other sources over the next three years, until the bonds are paid in full.”

The study also found that there will be costs associated with the management of the MERS “defined benefit plan,” where the benefit amount is calculated using a fixed formula based on an employee’s career history rather than stock market performance.

“To protect existing CMH employees in the defined benefit plan, MERS allows the new authority to carry the existing defined benefit plan to the entity,” the 2026 study said.

Although the contributions are currently managed by county administration, they have always been paid from CMH funds and managed separately by MERS.

“The cost for these CMH-related services is allocated to and paid by CMHOC, which is currently approximately $3.1 million per year. If CMHOC were to transition to an authority, it would likely transition away from receiving County-provided services and replace them with either their own employees, or outside contracted services. The costs for these replacement services are not yet known,” the study found.

Health costs rising?

Cunningham-White also told county officials at the Dec. 5 hearing that they need to monitor evolving policy on public employer health insurance costs, which could change depending on the outcome of a bill currently tied up before the Michigan Supreme Court.

“One word of caution is about health insurance costs, and I think this issue could affect county taxpayers in general. Keep an eye on a case currently before the Michigan Supreme Court, which could change the hard cap of public employer contributions to insurance,” Cunningham-White said.

HB 6058 amends the Publicly Funded Health Insurance Contribution Act and would require employers to contribute to certain medical plans and pay no more than the specific amount of annual costs, rates and reimbursement of copays, deductibles or payments into health savings accounts.

The bill is one of nine tied up in litigation after they were approved by the Legislature in lame-duck session of 2024 that current House Republican Speaker Matt Hall now refuses to send for Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s signature.

Under current law, the Publicity Funded Health Insurance Contribution Act acts as a "ceiling" of 80%, limiting how much taxpayer money can be spent on public employee premiums. HB 6058 would effectively turn that ceiling into a "floor," requiring public employers to cover 80% of the costs.

That change would affect all public employees, including state and local governments, schools, community colleges and public universities, and would effectively lift a healthcare contribution cap signed into law by former Gov. Rick Snyder in 2011.

In addition, HB 6058 would prohibit a collective-bargaining agreement or other contract executed on or after Jan. 1, 2025, from including terms inconsistent with the 80% minimum employer contribution.

All those factors made Cunningham-Clark concerned about the county thinking through the full financial consequences for which it was signing up.

“The fiscal headroom you think you might need according to law might be different in a few months’ time. Also, I’d like to hear a more robust strategy to maintain good coverage while controlling costs. Saying you’ll “aggressively negotiate” isn’t enough,” he said Feb. 5.

“Should we become an authority, CMH leadership and the commissioners who vote for it will own what happens next. Just remember the apocryphal Pottery Barn rule: ‘You break it, you buy it.’”

Conflicting information, confusing rollout

Most noteworthy about the entire process, since the CMH authority question was first raised publicly in November, is the urgency that Van Essen and Waterman emphasized in discussions, as well as conflicting information that has been shared in the two studies, the public meetings and the county’s own website.

Fast timeline

At the November discussion, Van Essen insisted that presenting the idea in no way obligated commissioners to act.

“If you go down that process, there will be three public hearings that have to be held where there will be an opportunity to debate the pros and cons with the community and amongst yourselves,” the attorney said. “And then a resolution would be passed before you create an authority. So it's a long public process to go down that road; today is really just an introduction as to the alternative and whether you're even interested in starting that debate.”

That “long process,” however, ultimately materialized to be 44 days, from when the board voted at a special meeting on Jan. 13 to hold public hearings to when the majority will presumably approve the resolution to formalize the conversion process on Feb. 26.

A Dec. 18 meeting was filled with questions from the public and some commissioners as to why the public hearings needed to happen immediately.

“For the sake of clarity, can I ask you to provide us a one-sentence statement describing a stated reason for this proposal? We, the public, have nothing at all in writing from you, the commission, giving us a rationale for this,” said Allendale resident Becky Patrick during public comment.

“This would be a momentous undertaking. Not only is it a momentous undertaking all on its own, it would be compounded by doing it at a time when CMH is already very financially fragile and a time when there is much confusion and uncertainty about the statewide structure of mental health care.”

“Everyone involved deserves clarity on your reasons before you put this matter on the fast track,” Patrick said. “I therefore ask you to table this matter unless and until you provide us that clarity.”

Some commissioners agreed, pointing out the updated study had not yet been provided to commissioners, let alone to the public.

Despite the lack of documentation justifying the conversion the current board majority, led by six moderate Republicans, appeared to support Waterman’s suggested dates of Jan. 7, Jan. 14 and Jan. 15 to hold the required public hearings before commissions could voted on a resolution to approve the transition.

“Part of it, for me, is it's about the image that we are conveying to the general public,” said OI Commissioner Allison Miedema. “So I think what we're missing here is by scheduling public hearings and going ahead it is making it look like we are, in a sense, affirming moving to an independent authority. It doesn't mean that we are, but it does give the public the perception that … by skipping steps, I believe were out of order.”

“I believe that very much we should be waiting for the study, so I'm actually going to make a motion to table this resolution indefinitely, at this point in time.”

Commissioner Jim Barry, a moderate Republican, said “a little surprised at what some of the folks seem to know and what they sort of didn't know.”

“Not everybody was paying attention to our last meeting where this got a lot of discussion,” he said of the Nov. 21 special meeting where the board planned to go into closed session, but stayed in open session.

Waterman said if the hearings could all take place in January, the information could be ready for commissioners to make an informed vote as soon as the end of that month.

He said his urgency came from a budgetary perspective, as discussions would start in earnest by March to create the county’s budget for the 2026-27 fiscal year, which begins Oct. 1.

“If there's not support on this board for the 7th, 14th and 15th, I'd be looking for something maybe later in January or by mid-February, because I know the clock to a degree is ticking and you guys need to have direction from us. And we need input from the community. So let's give them the most amount of time to make that.”

Ultimately, the board voted to table setting public hearings until its next meeting on Jan. 13, which allowed the 2026 study to be provided to the board and the public.

Residents, however, still had questions.

“From my perspective, the report included in the packet fails to answer several questions I believe the board should be asking before it can make a fully informed decision,” said Karen Obits, of Spring Lake. “These questions pertain to three areas. First, the reasons for increasing CMH deficits. Second, the reasons for the perceived increased financial risk to the county. And third, the less-than-clear picture of potential impact to CMH services.”

Obits also said she would like to see how the majority of Michigan's counties are doing, after converting to authorities, even if some did nearly 30 years ago.

“It would be helpful to be able to review available data on what those counties experienced in financial costs and any resulting impact on the availability of services and comparative quality of services rendered,” she said. “I'd also like to know what kind of impact there may have been on their ability to recruit and retain qualified staff.”

As the board prepared to discuss the newly available study, Waterman said it would be up to residents to access it online and read it.

“We feel that the report speaks for itself,” he said. “I also do have some talking points that summarizes the report if the board would like to hear that or for the benefit of the public, but we were not planning on making a formal presentation on the report's contents.”

Again, some commissioners — most of the four OI members and the board’s lone Democrat — described the process thus far as “rushed.”

“I would just say that it seems very rushed to me, this process,” said OI Commissioner Sylvia Rhodea. “I understand the high level of concern in why we're looking at it right now due to the fiscal impacts. But I don't think we have all the answers provided still to give us … I would call it a fire alarm approach. I'm not seeing that. I'm not seeing a fire alarm approach and for that matter, I don't think we should be taking a fire alarm approach when we are dealing with the most vulnerable families throughout our county.”

Questions continue

Doug Zylstra, the only Democrat on the board, was concerned about the $3.1 million in CMH-related services tied to the defined benefit plan services.

“The $3.1 million that is currently being allocated to CMH once they become an authority will no longer be allocated to CMH, but we will still be paying those $3.1 million in expenses, right? … And those expenses will then be reallocated to every single department.”

County Finance Director Karen Karasinski confirmed that Zylstra’s assessment was correct, but that there could be a reduction in costs depending on how the pension bond is managed.

Despite the debate, the board voted 6-5 — the majority for and OI and Zylstra against — to move forward with holding the public hearings:

- Jan. 19: Spring Lake Community Center

- Jan. 20: Georgetown Library

- Feb. 5: Public Health Complex in Holland

Those hearings also were confusing to some residents; despite either live streaming or recording and then posting most, if not all, of its public meetings on its YouTube channel, county officials only recorded and posted one of the public hearings.

A tale of two studies

There were also fundamental differences between the two studies conducted 10 years apart, and not just because they yielded conflicting conclusions.

Included in the 2016 study was the involvement of what is now known as the county’s Department of Strategic Impact, which acts as a strategic planning, evaluation, and performance improvement unit, focusing on long-term initiatives to enhance county services, infrastructure and community development.

DSI was not involved in the curation of the 2026 report and DSI Director Paul Sachs has not publicly spoken about the authority conversion question.

Sachs declined to comment for this story.

Another key difference between the two documents is the wealth of financial information in the 2016 study versus the near lack of financial data in its 2026 counterpart. In the 2016 report, dollar amounts comparing various revenues, costs and budget considerations totaled 180 citations and outlined areas of savings versus projected cost increases.

The 2026 study contained just 11 such citations (not including charts) and did not provide specific savings versus cost increases, meaning current budget numbers have not been made available to the public.

The Washtenaw argument

A key argument in both studies revolved around the unique situation in Washtenaw County on the state’s east side, coming to opposite conclusions.

In 2000, Washtenaw opted to convert its CMH department to an authority, which created a partnership with the University of Michigan, whose campus is located within the county.

In 2015, however, the county opted to convert back to a county department, citing a mix of financial instability, administrative friction and a desire for more direct local control.

Ottawa’s 2016 study pointed to the financial instability of Washtenaw’s agency model as a cautionary tale to not convert at that time.

“If there are financial problems in the future, it is likely the county would still be approached to cover budgetary shortfalls even though all authority is vested outside of the county,” the 2016 study said.

Sheehan, the head of the Mental Health Association of Michigan, said Washtenaw was struggling, at the time, to set competitive wages and exert local control.

“I think what they were finding was the authority didn't have enough money to pay the wages of the county, so they brought them back. There are other reasons … financial, control, etc., but they brought them back,” Sheehan said.

By 2018, Washtenaw County CMH was facing a projected $16.4 million deficit. The county argued that this wasn't due to local mismanagement, but because the state’s funding formula for Medicaid was fundamentally broken. It then took the rare and aggressive step of suing MDHHS, claiming the state used a flawed actuarial process to set reimbursement rates.

This lawsuit was a "nuclear option" because CMHs and the state usually settle these disputes through administrative appeals. By suing, Washtenaw was publicly challenging the Snyder Administration's management of the CMH funding system.

Washtenaw argued that the state was essentially forcing counties to use local tax dollars — it created a countywide mental health millage in 2017 — to cover what should have been a state Medicaid responsibility.

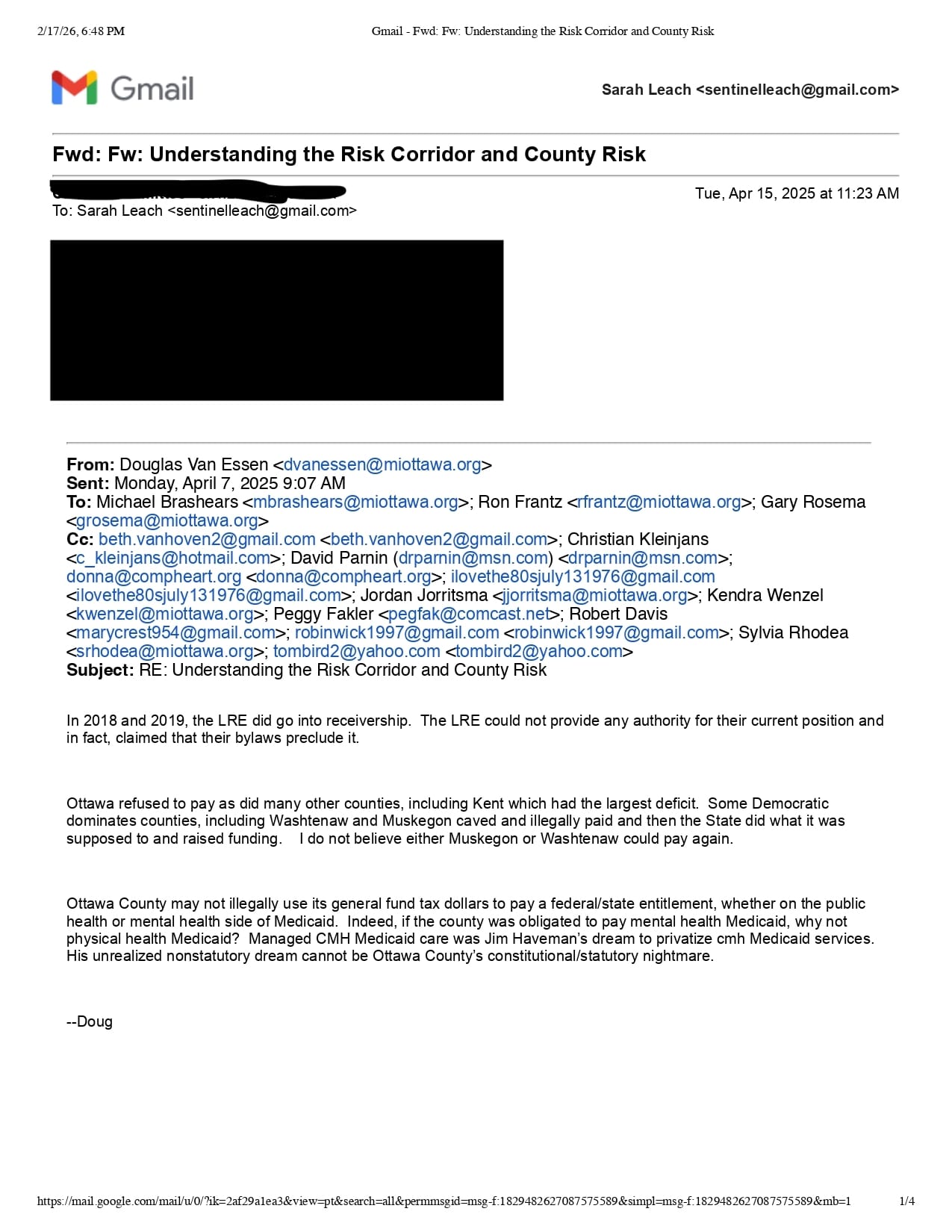

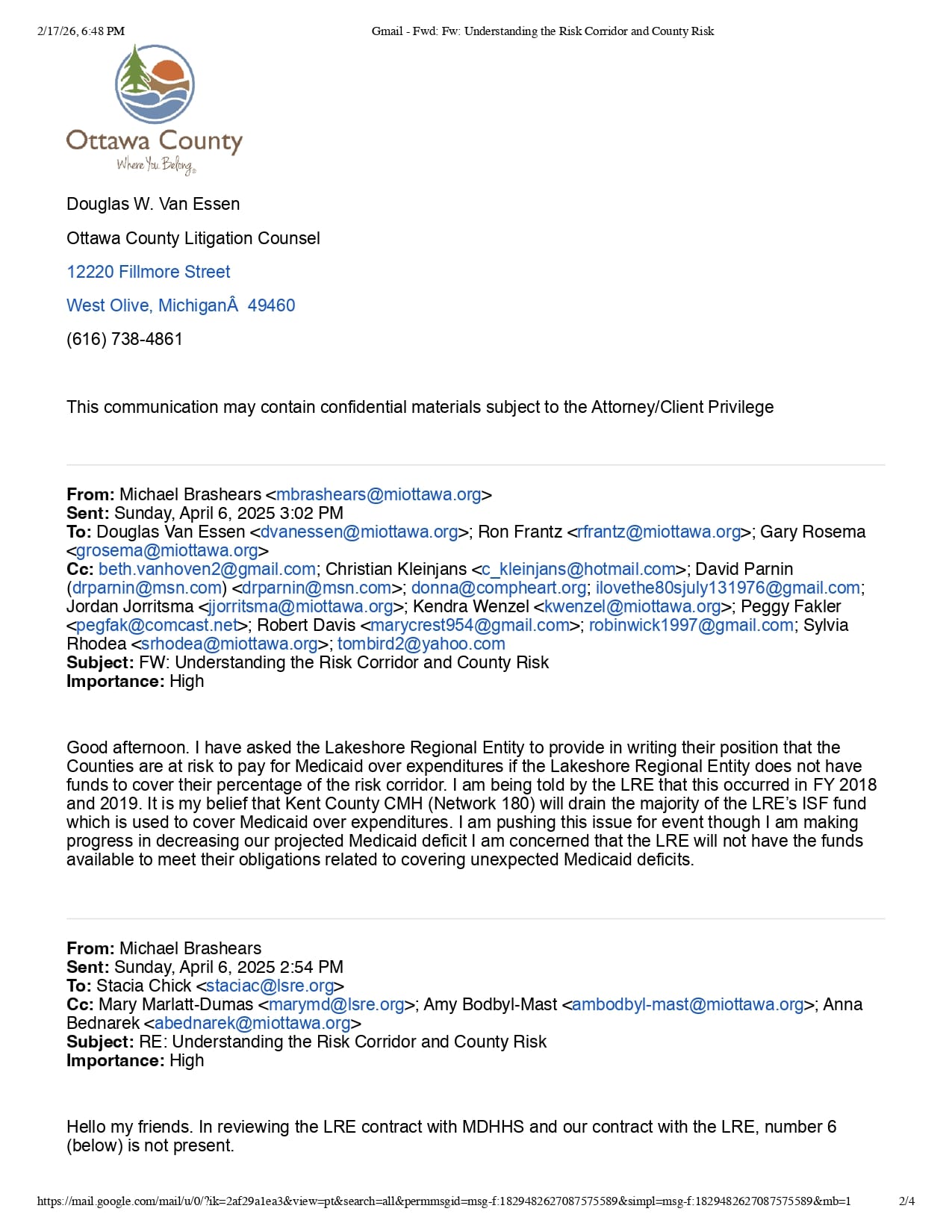

Van Essen has discussed the Washtenaw example, along with a similar lawsuit filed by a Muskegon County resident who claimed MDHHS failed to provide federally mandated, intensive home-based and community-based mental health services to children on Medicaid.

In 2018, Van Essen said several county CMH departments faced stark deficits that year: Muskegon ($12 million), Washtenaw ($10 million) and Ottawa ($2 million).

He said he discussed the situation with Muskegon and Washtenaw and urged them not to pay out of their general funds.

“We discussed this as three counties in this situation, and I told Muskegon and Washtenaw, ‘Whatever you do, do not pay this out of your general fund. Our position is we have no authority to take that money and spend it. Let's hold fast to that, because that will force a problem, but ultimately that's our defense … is that the state's got to solve that problem, not us,’” he told Ottawa commissioners Nov. 21.

He said the only reason the counties were in that situation was because they were still county departments.

“We discussed this as three counties in this situation, and I told Muskegon and Washtenaw, ‘Whatever you do, do not pay this out of your general fund. Our position is we have no authority to take that money and spend it. Let's hold fast to that, because that will force a problem, but ultimately that's our defense … is that the state's got to solve that problem, not us.'" ~ Doug Van Essen

“Why was it just the three of us? Because there's a state statute that says if you're an authority, you have no risk. Every other county that was facing a deficit was relaxed,” Van Essen said. They assumed the state would have to pick it up because there's a statute … that gives them protection. But we are on the front line.”

The other two counties “caved,” according to Van Essen, but with an intentional strategy of asking the state to cover the tab.

“They did what I think is illegal. They said, ‘Don't worry, guys, we're going to sue,’” he said.

That argument didn’t work in the courts.

“The Court of Appeals said, ‘Well, you paid. You voluntarily paid.’ So, they lost that case.”

At the Jan. 13 meeting, Van Essen told a slightly different version of the Washtenaw-Muskegon scenario, this time saying the counties “in order to avoid the hundreds of lawsuits that were being threatened against them,” although he didn’t provide any specific examples.

“We would be exposed, our general fund, to that kind of pressure and that's why there is a certain immediacy to continuing this discussion,” he said.

Van Essen said Ottawa was able to avoid a confrontation with the state.

“We were able … to eventually wipe it out. Thanks to (Karasinski's) expertise, so we didn't have quite the pressure they had.”

Website information

While the county was hosting its three public hearings in January and February, it published a page on its website featuring a “Frequently Asked Questions” section about the question to convert to an authority.

Several slides contain inaccurate or missing information — or lack context — which several public speakers pointed out during the three public hearings.

One slide poses the question: Are there examples where a CMH authority has (sic) deficits and the state has stepped in to cover costs?

In the county’s answer, it said the authorities “presented their deficits to the state and it increased funding to cover those deficits. The county departments, including Ottawa, Muskegon and Washtenaw, were left to cover the deficits with their own resources.”

The explanation is inconsistent with Van Essen’s explanation of Muskegon and Washtenaw intentionally using their general fund dollars to make up their deficits, as well as his recounting of Ottawa not confronting the state and finding accounting adjustments to make up the local $2 million shortfall.

Another slide asks: How would accountability of the CMH work under an authority structure?

In its answer, the county said the program would be exclusively accountable to the CMH board of directors, saying “the only accountability the Board of Commissioners has over CMH is regarding millage funds” and that the board would continue to appoint or remove members of the mental health board, if needed.

While both of those statements are true, the county board also has the option to convert the authority back into a department if it so chooses.

It also has final approval to ratify any ballot language that countywide voters will see, including the renewals of the countywide CMH millage.

That millage question is noted in a separate slide that asks who approves millage requests — the CMH authority or the board. The county said the county board; although the final authority in approving the language, the authority’s board would originate and approve the language first, which was not included in the FAQ.

In a slide that asks for side-by-side comparisons between a department and an authority, the county said there “are too many variables to show a side-by-side comparison over the years.”

The answer seemingly conflicts with the county’s self-produced 2016 report that offered numerous specific budgetary considerations, including where costs would increase and where savings would be realized.

Another slide asked if there was a state law that outlined how authority transitions are managed and documenting the one-year timeline Van Essen told commissioners.

In the county’s answer, it cited MCL 330.1220, which is the statute that governs the termination of a county's participation in a community mental health services program, according to Michigan Legislature’s website. The statute that the legislature lists outlining such transitions is MCL 330.1205, and no timeline is included in the language.

Van Essen did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.

What might be in play

There are other, less obvious, outcomes if the county CMH department were to convert an authority.

Preventing political meddling

One result of approving the conversion to an authority would be removing the board of commissioners’ current role of giving final approval on internal CMH processes and procedures, including policy setting, new and upgraded positions and receiving grant funding.

During Ottawa Impact’s tenure as the controlling majority of the county board in 2023 and 2024, there were numerous delays on these processes for CMH as well as the county’s Department of Public Health.

One example was the 2023 Community Health Needs Assessment, which includes several surveys and stakeholder interviews to gather input on the countywide health need trends every three years. It's a partnership between the health department, Holland Hospital, Corewell Health Zeeland Hospital, Trinity Health Grand Haven, United Way of Ottawa and Allegan Counties, CMH and other organizations.

The contract for the CHNA was initially approved in December 2022 by the outgoing board and was ratified Jan. 10 by the new board with Ottawa Impact at the helm.

In February, however, OI commissioners appeared to backtrack on the decision, focusing on the already approved memorandum of understanding, which detailed how funds would come from hospital partners, through the county, to the vendor.

The discussions heavily focused on the “appropriateness” of specific questions posed to adults and youths — depending on which survey was being discussed — and the board postponed the vote until May while they explored potentially ways of canceling or renegotiating the contract in order to control what questions were allowed to be asked.

Those talking points would define the OI-led board for 2023-24, with numerous contracts scrutinized — particularly when it pertained to health or mental health — often criticizing vendors if their organization or materials didn’t align with the far-right Republicans’ values.

Another example of exerting political influence was the OI majority rejecting several grants from the state and federal government that would have benefitted mental health programs and their recipients.

In July 2023, the health department requested authorization of an $8,000 contract with GRIT Media to run a social media campaign raising awareness for ManTherapy in Ottawa and Allegan counties. The campaign would be funded by cross jurisdictional funds from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services with no cost to the county’s general fund.

ManTherapy is a website that uses humor to connect working-age men with mental health resources as a method of suicide prevention.

The campaign would have run in August and September, had the board accepted the funds.

However, the idea was rejected by Ottawa Impact over concerns that the campaign could “target children.”

“I’d love to see an opportunity that we can (use) to promote men’s mental health in another avenue,” said Miedema, an OI commissioner.

Marginalized communities were of particular interest to the OI majority as well, with programs, funding and other resources under frequent inspection.

In February 2023, the county informed the Holland-based LGBTQ nonprofit Out on the Lakeshore that it was approved to receive $8,000 in grant funding provided by the Michigan Public Health Institute. But the funds didn’t come as expected.

Several organizations that should have received funding, including $12,500 for a Black doula program, in fact experienced significant delays without explanation.

The memorandums of understanding were written and ready, waiting solely on a signature from then-board chair Joe Moss, the founder of Ottawa Impact.

In May, Moss notified the organization that MOU for its grant was "signed," but Moss didn't use his name. Instead, he signed it "vi coactus," Latin for "compelled by force" or "having been compelled." (He signed it with his actual signature three days later.)

“It's curious what organizations were not funded, and the organizations that were,” said Susan Mendoza, then board chair of OOTL. “It reinforces perceptions of how minoritized populations will be supported by county government, how they're valued and how they're seen.”

Influence through CMH board appointments

The OI majority didn’t just leverage its influence on the board of commissioners — it also appointed its own members or political allies to the CMH board of directors to influence how policies and contracts were curated before reaching the full county board.

In September 2023, the CMH board was tasked with approving 63 annual contracts for the 2024 fiscal year, which was set to begin Oct. 1.

Among them was the $290,799.92 contract for the Momentum Center, which has drawn the ire of Ottawa Impact and its supporters over its focus on social determinants.

The organization was the frequent target of OI supporters, claiming its programs and policies were “creating racism” and “grooming children,” something Executive Director Barbara Lee VanHorssen firmly denied.

Then-commissioner Gretchen Cosby, an OI member who was appointed to the CMH board by Moss, denied targeting only the Momentum Center — one of four social recreation programs that receive funding from the county’s mental health millage — although she admitted to discussing the center’s contract specifically with two of her fellow OI commissioners who also were appointed by Moss to the CMH board.

The doubletalk drew the ire of other CMH board members.

"You say it's not about the Momentum Center, but we're only talking about the Momentum Center," said Terry Goldberg, then-CMH board secretary. "We need to get over this target. We're making judgments on this group."

When then-CMH board chair Vonnie VanderZwaag asked if Cosby intended to discuss funding for all social recreation programs that have contracts with CMH, Cosby was unprepared to answer: "I haven't actually thought that through."

The four social recreation contracts were approved for three months of funding, rather than a full year, as requested.

In December, after much public outcry at CMH board meetings as well as county board meetings, funding for all four programs was approved in a 5-3 vote — only after an OI commissioner left the meeting early.

If the county converted CMH into an authority, the county board would only be able to influence the through making CMH board appointments — which state statute dictates lies with county commissioners — or by voting to bring the authority back in-house as a county department.

Sheehan said the conversation to convert varies county to county and what specific financial and political dynamics are in play.

“I tell people, the non-authority CMHs across the state are in very different political worlds: Lapeer, Muskegon, Ottawa, Washington, Macomb. They couldn't be more different from each other, and yet they all have stayed part of the government. Some people say, ‘Well, conservative counties have departments, not authorities, or progressive counties do,’ and that's not true.”

Controversial hiring, contract

Also in question is the manner in which Brashears was hired under OI’s leadership.

Brashears, who previously served as the CMH executive director for Ottawa County from 2008 to 2013, was re-hired as executive director of CMH on July 26, 2024, after serving as interim director since May.

When he left the role in 2013, then-deputy director and longtime CMH employee Doyle was promoted to the top position, where she remained for more than 10 years.

In early 2024, Doyle took an extended medical leave before announcing her retirement. Brashears, who was then serving on a steering committee as the mental health millage neared its 2026 renewal vote, was tapped to serve in the interim role by Cosby, who had recently been chosen as the CMH board chair.

“I was asked if I had formal interest by the CMH board chair, Gretchen and then that's how I kind of got back into it.” Brashears told ONN in a December interview.

The CMH board’s executive transition committee, however, did not conduct a search despite calls from some members to explore options.

The transition committee, also led by Cosby, met July 1, 2024, when Cosby said Brashears was the only candidate after CMH Deputy Director Anna Bednarek withdrew her name from consideration. Despite having only one candidate, Cosby insisted a search wasn’t necessary.

“From my perspective, we’re very fortunate to have him step back in. He knows the organization,” she said during the July 1 meeting.

Chris Kleinjans, who was then a sitting county commissioner as well as a legacy CMH board member prior to his election, attended the July 1 meeting — despite not being selected to serve on the executive transition committee — said he felt Cosby and others were rushing the process.

“I've become concerned that we are expediting the goal of finding the best new executive director for Community Mental Health of Ottawa County too quickly,” Kleinjans said during public comment.

Then-CMH board member David Parnin, who was on the transition committee, said he would have felt more comfortable waiting longer to gauge the morale of CMH staff and how they felt about Brashears returning to his former role — after numerous controversial statements about mental health and CMH were made by OI officials and supporters.

The committee unanimously recommended the permanent appointment of Brashears.

Brashears told ONN in January 2025 that he wasn’t involved in the political division that seemingly dominated county government during the OI majority years.

“I work with everybody that's part of the county, and I've been very clear that my focus is on the job of folks — politics above it. I stay out of that because I don't control any of them. So there is a war going on between different factions of county government that I will tell you has had an impact to all the employees,” he said.

He insisted that if the CMH board had opted for a national search, he would have been willing to engage in the process.

At the beginning of the July 26 regular CMH board meeting, Cosby moved to amend the agenda at the last minute — a hallmark of the OI majority during their tenure — to include the permanent appointment of Brashears to the director role.

The resolution that was approved read: “To appoint Dr. Michael Brashears, for a term of 5 years, as executive director of Community Mental Health of Ottawa County, to be memorialized in a written contract, which the Chairperson is authorized to sign.”

No contract language was included in the packet for board members to review and a compensation figure wasn’t discussed, meaning the only component approved by the CMH board that day was the term of five years.

As of publication, the contract had not been added to the July 26 packet. ONN received the contracts through a Freedom of Information Act request.

“During the July 26 meeting where Dr. Brashears was confirmed as CMH director, no mention of the details of his contract were revealed other than its length was given by (then)-chair Cosby,” Kleinjans said.

“The executive search committee as a body never brought one to the full board for consideration and discussion. A review of my email indicates that a copy wasn't included in the board packet for the meeting nor was it sent out by the executive search committee as a stand-alone doc,” he said.

Three days later, on July 29, Cosby signed Brashears’ new contract with an annual pay rate of $260,000 — meaning he will earn $1.3 million through 2029.

Prior to the vote, Rhodea asked Cosby about the term length of the contract.

“Just because I’m new to this … the five years … is that typical?” she asked.

Cosby said a five-year contract was not unusual.

“I have worked with corporation counsel and then also Dr. Brashears and we looked historically at other executives and this is not an abnormal timeframe,” Cosby said.

In fact, the previous contracts for Brashears and Doyle — dating back to Brashears’ original contract in 2008 — were for three-year terms, not five.

Because the CMH board never saw or approved an official contract with Brashears before Cosby signed it, it could initiate a legal review of its enforceability.

The agreement also appears to conflict with the CMH board’s own bylaws, which address the ratification of contracts, outlining that the board chair is allowed to execute an agreement, but must do so in conjunction with the CMH board secretary.

If the county were to convert to an authority, Brashears’ current contract would transfer over to the new entity, according to current CMH Board Chair Tom Bird

The contract and its legality is under the purview of the CMH board, regardless of if the organization remains a department or converts to an authority, however, the board of commissioners is still able to wield some influence on the board through member appointments — two of which are scheduled to be made this spring.

When Miedema, an OI commissioner who isn’t on the CMH board, pressured current county board Chair Josh Brugger on Jan. 13 to reappoint OI commissioners Rhodea and Kendra Wenzel to the mental health board, Brugger was non-committal.

Brugger clarifying that they're both fulfilling their terms, which end in March. The new terms don't start until April.

— Sarah Leach ☮️ (@ONNLeach) January 13, 2026

“I guess I don't understand why we're not letting those two commissioners fill the term because that's what our motion was,” Miedema said of a vote taken by the previous OI-led board. “And I would say that there was disagreement on how that took place. So, I think we wouldn't want to open those seats up for the general public if this board of commissioners wants to continue serving on that board.”

Brugger clarified that both Rhodea and Wenzel are fulfilling their terms, which end in March. The new terms don't start until April.

“Per statute, Commissioner Wenszel and Commissioner Rhodea automatically finish their term, until March 31, 2026,” Brugger said. “If they are reappointed now, per Commissioner Miedema’s motion, it would be for a three-year term beginning April 1, 2026, through March 31, 2029.

“The only reason this one was left out … the primary reason that I was not rushed to do this one … is that I hadn't yet made up my mind on who I was going to recommend for this committee. And because unlike all of the other committees, this one does not have a starting term until April. And so, for me, I had another 30 to 60 days at the most to sort through this.”